This post was inspired by the most memorable occasion of missing my camera – or, put otherwise, the most memorable birds I never photographed. It also offers a glimpse of one of Croatia’s multiple car-free islands. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs in this post were taken in Silba, with a 1st gen iPhone SE during late October and early November 2022.

In the first two instalments of Nonmotorized Trails, I looked at experiences of connecting with wildness (especially wild birds) in my home base of Columbus, Ohio. In the present instalment, the travel blogging shall begin. Before I take things too far with bird-heavy content, I have decided to make a post that underscores a caution that I raised in the about page: I always travel with only carry-on luggage, even though I stay abroad for months at time, so it shouldn’t be too surprising that sometimes I’ve decided not to pack my “real camera” and telephoto lens. As a result, my recent life encompasses several multi-month intervals of overseas saunters without a single decent bird photograph to show for them. Most of the time, I did not regret my decision not to carry the extra weight and bulk, but there have been exceptions, and the time I missed my camera the most was when the goldcrests came to Silba…

But there was something equally significant about my month-long sojourn in Silba — a car-free island in Croatia’s Zadar archipelago — in the autumn of 2022: the journey to Silba heralded a “return to form” after I had drifted too far from the commitment to escape car-dominant infrastructure that had driven me from America in the first place.

1. Background: The Long Road to Silba

As I described in my Thoreau-inspired June 2022 blog post “Around the World for a Ten Miles’ Radius,” I never became a “digital nomad” because I desired a life of travel. On the contrary, I wanted to live in a place where I would never need to venture too far from my front door (on foot of course) to meet all of my basic needs, including not only shopping but also sauntering under skies unpolluted by exhaust fumes, artificial light, and the noise of machines. In the US, however, development patterns have created an artificial forced choice between the Scylla of confinement to a large city and the Charybdis of reliance on an automobile for nearly all activities (including merely going for a walk on a trail instead of the road). This is not the case in much of Europe — as surprising to me as that was when I first went abroad. So I went back.

On my second attempt at becoming a digital nomad, I lasted much longer, and my first major breakthrough was a lesson in tolerating imperfections. I had fled a major city, full of all the typical urban noise and light pollution, as well as a thin-walled apartment building. But — long story short — it turns out that not everyone who rents or owns a summerhouse in Europe does so out of a desire for silence and seclusion. For some, a summerhouse is a place to host loud parties with greater immunity than a residential district. For some, it’s a place to nurture a hobby of massacring flora with noisy machines. And even when neighbours are absent, it is always a gamble as to whether they’ll have left on bright security lights, rumbling HVAC units, or so on. I was forced to let go of perfectionism and concede that, even in the Old World, one cannot bank on finding a holiday home with a total absence of traffic noise, artificial lights, audible neighbours, or even humanity’s most loathed invention: the leaf blower.

But, another long story short, I took my lessons in tolerance too far. By the end of the first year, I found myself living in a cottage with a view of tarmac and parked cars out the front window and a view of tarmac and parked motorbikes out the back. From the bedroom window, I could occasionally see a corvid on a roof across the street, but for a large part of each day, the soundscape was dominated by the revving of the engines of the motorbikes, which were always coming or going (or idling) outside the adjacent hotel. I had to admit that I had started to sell myself short; this was not what I wanted.

And it was in that context that I resolved to return to small car-free islands after my next visit back to the US. Beginning with Croatia. Beginning with Silba.

2. Sauntering on Silba

Memories are easily tainted, whether for good or for ill, and it can be useful to refer to contemporary correspondence to see what one was actually thinking at a certain time in one’s life. When I resolved to write this post, I could easily remember the best of Silba — the swimming cove, the night walks, and of course the goldcrests — as well as the things I eventually missed (e.g. better coffee, a bigger food selection, or being able to easily communicate in a common language with the majority of people). Before I looked back at emails and social media posts, however, I had entirely forgotten that my trip to Silba began with a multi-day WiFi outage combined with difficulty in finding a pleasant walk that didn’t terminate at some impassibly overgrown segment between the island’s ubiquitous dry stone walls (its historic mocire).

Despite these hurdles, I settled into the island life quickly, and according to my first post to Facebook after the restoration of the WiFi, I seemed clearly happy with my decision to come to the island:

This morning, I finally found a walk on Silba – in the northwest of the island – where I could feel at peace and remember, if only for the moment, why I opted into this insane game [living as a digital nomad]. What the pictures fail to capture is the absence of anthropogenic noise pollution, the fresh air, the chirping of birds and their wingbeats, the scurrying lizards, the complete human-wise solitude. [...] I am caged without the ability to slip out the backdoor and walk to such quiet and solitary places. [...] I plan to return to part of this for night walks as well. Silba is not a Dark Sky Island, and it shows in the very poor lighting design in the town and resort areas. But the first part of this road leads pretty quickly to an unlit beach (and, compared to other nearby roads, has somewhat fewer rocks, sheep carcasses, etc., to trip over in the dark).

I would go on to explore nearly the full island on foot during the month I was there — the walk down to the southern tip, once I found it, was also quite nice — but it’s that go-to walk that I remember best, both at night and day.

2.1 A Night Walk in Daytime

There’s something a bit odd about saying that I missed the Milky Way while living in the city, giving that I was in fact living in the Milky Way entire time. But you know what I mean, and if you’ve ever experienced the enthralment of gazing into the depths of the galaxy on a dark and quiet night, you will also understand why I missed it — and why it didn’t take long for me to go back out on that night walk.

Here is how I described a couple of my experiences at the time:

Silba is proving to be a worthwhile place to enjoy warm evenings under clear skies with expansive views of the Milky Way – a place, that is, to absorb some of the final clear views of the night sky before satellite constellations obscure all. [...] As predicted, the northwest road out of Silba town was an ideal option for a dark-adaptation stroll, with no streetlights, relatively few trip hazards, and a light surface colour that provides good contrast even when operating only on rods. I could easily walk without a torch, under only starlight and the diffuse ambient glow of light reflected from space junk. The island’s absence of cars is a welcome safety feature at all times, but perhaps especially when walking in darkness. [...] My chosen destination was a little cove by the sea. More often than not, unfortunately, the descent to the water's edge brings only the intrusion of more gaudy artificial lights – whether cities on a distant shore, brightly illuminated ships, or offshore wind farms – and one is better off remaining inland to experience purer nightscapes. In this case, there were some distracting lights from Premuda, so I turned my back to face inland and upward as I listened to the lapping waters. I saw a shooting star, and I wished the first wish that came to mind, which might or might not have been some not-so-nice thing regarding Elon Musk.

I have enjoyed some glorious nocturnal sauntering on Silba […] around the time of the new moon with clear skies and mild weather. My night walk on my birthday was a unique experience, and enchanting in its own right. There was a rather heavy fog that night, thick enough to completely obscure some rather obnoxious lights from Premuda that are usually visible from the western shoreline. So, happily, I was able to look out to sea and see nothing but its dissolution into the dark grey, rather than to face the intrusion of point sources of artificial light.

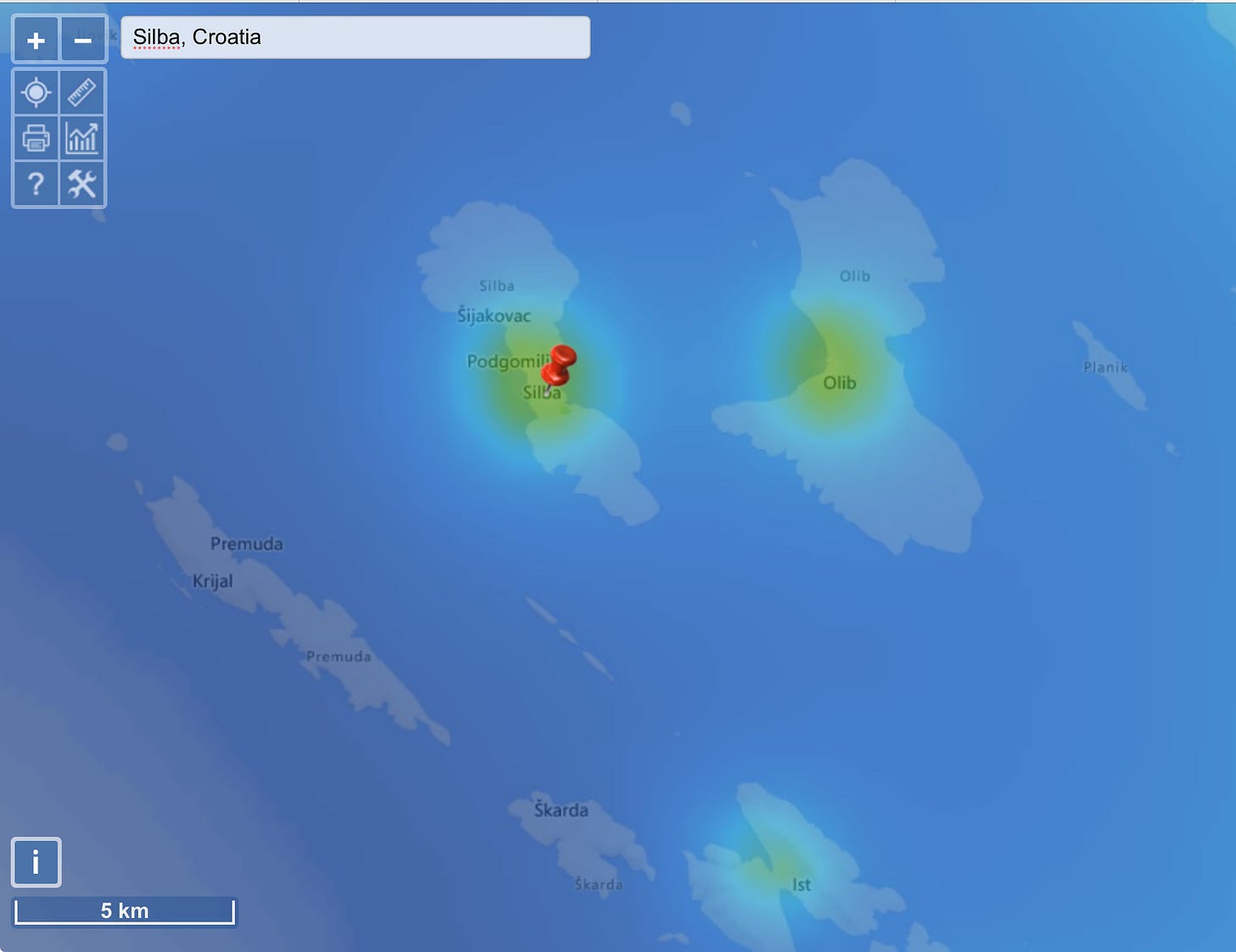

I did not have a good enough camera or lens for bird photography on Silba, nor did I have a good enough camera or tripod for night-sky photography. Thus, the reader must rest content with this daytime photograph of my favorite night-walk destination, plus two light pollution maps (from www.lightpollutionmap.info) comparing Silba to Columbus. Granted, a full map of Ohio might have offered a more striking contrast: within a short walk from “downtown” Silba, one can reach skies that are less light-polluted than even the most remote (and deepest red) rural areas in my home state.

2.2 A Private Public Swimming Cove

In the daytime, the most memorable aspect of that walk — even more than the fruiting strawberry trees, scurrying rock lizards, scents of aromatic vegetation, and glimpses of the most clear blue water I’ve ever seen — was stumbling across a placid and idyllic beach that I’d come to call my “private swimming cove” in personal correspondence. Well, that was rather inaccurate since it’s open to the public, but it would be understatement to say that it was never crowded. I wrote, “I attempted my first swim on Silba today, off from an isolated beach with a small portion of sand, instead of only the more common rock or mounds of dried seaweed. It was cold, yet enjoyable in the quiet and secluded setting with excellent views of the evergreen shrubbery that is so lush in the northwest of the island,” and about a later swim, “the glow of the sea [at the golden hour] in the setting provided a welcome distraction while acclimating. A blissful and enchanting interlude between the tractors and construction work of the afternoon and incessant dog barking of the evening.”

Among the uninitiated, the first reaction to comments about swimming alone or walking in the dark is often “that sounds dangerous.” To be sure, it is imperative always to be attentive and aware of one’s surroundings when engaging in such behaviour — in part for safety, in part because such mindfulness is the gateway to drug-free existential bliss in feeling one with nature and the universe.

3. Safety Third

In ordinary conversation, it’s not even necessary to mention swimming alone or walking at night on unlit streets; to trigger paternalistic fear in the eyes of the world, it’s only necessary to mention travelling alone while female. Whenever someone asks “Aren’t you scared doing that,” I always want to point to their personal automobile and exclaim, “Aren’t you scared driving that?!” The thing is, I do worry about safety, and I am very far from fearless — and one of the things I find most frightening of all is also one of the most objectively deadly: motor traffic.

Upon my arrival to Silba, and thus my return to the car-free world, I posted the following on Facebook:

When I come to a place with no or few cars, it seems immediately natural, how a town should be. The moment of shock comes when I go back to living in a place where I cannot simply move about freely, but instead find motion constrained by traffic signals and/or waiting for gaps in the passage of streams of fast-moving two-ton hunks of metal. As a pedestrian, it feels stifling no longer to ‘own the road’ but to be crammed into the margins [...]. If you already think walking or biking in a car-based city is irritating or frightening, imagine how it is after months of living in settlements with safe, unconstrained, people-first movement patterns.

Now, even in car-dominated areas, I have always maintained that it is the pedestrian who enjoys the greater genuine freedom of motion. Most obviously, the pedestrian is not physically strapped into a chair, but instead enjoys full use of her body and limbs. If a motorist wants to stretch, he must first diverge from his route, find a safe and legal place to pull off the road, park, get out of the car, etc. The pedestrian can just stop and stretch. Furthermore, if the motorist sees something interesting by the side of the road, he typically cannot stop in his tracks without potentially fatal consequences. As I noted in my previous post, the pedestrian enjoys much greater liberty to “make a hasty decision to stop and watch birds without needing to find a parking spot, blocking the road, or putting others at risk of rear-end collision.”

The personal automobile offers “freedom” to go faster and further, but what good are speed and distance on an 1500-hectare island with a single central town designed to accommodate the needs of a few hundred non-car-owning residents? The two small supermarkets, ATMs, and several cafés (depending on season) are never that far away.

Shortly after my arrival in Silba, I said the following in some personal correspondence: “it is good to live once again in a small, insular, car-free community. While such a setting does not imply an absence of stress and agitation, of course, it does confer a sort of baseline of calmness and placidity that just isn’t possible in most of modern industrial civilisation, in my opinion.”

Car-free living is sometimes stigmatised as a virtuous act of self-sacrifice. Anyone who holds this unimaginative stereotype might find it enlightening to spend some time on a car-free island in the developed world. Perhaps they will then realise that car-free living can just be part and parcel of slowing down — “living on island time,” as we say— and understand why some of us consider it a more pleasant way of life.

Now, in principle, the slow-paced and laid-back lifestyle of a car-free island could be emulated in a small and self-contained (if import-reliant) community anywhere — not necessarily surrounded by sea. Granted, the waters of the Adriatic are fine indeed.

4. Imperfections in Paradise

As the astute reader will have discerned from some of the passages of quoted text in §2, Silba wasn’t always as idyllic as it might seem from the clear blue waters lined by charming Mediterranean scrub. For example, although Silba is a good place to visit to see dark skies, it is a circumstance that we philosophers might describe as de facto rather than de jure. Unlike the “official” Dark Sky Places to which I alluded, Silba is governed by no ordinance that prohibits unnecessarily bright or unshielded external lights (for example). It just happens to have easily accessible dark skies in virtue of being a fairly remote island with a small population contained within a fairly small part of the island’s land area. Similarly, Silba’s quietness seems to be de facto rather than de jure (with some exceptions, e.g., construction work is prohibited during high season — presumably so that tourists can enjoy more quiet and relaxation — which of course is not when I visited). Due to the island’s remoteness, small population, and relatively small developed area, it’s usually easy to walk away from the noisy tractors, construction work, lawn equipment, and barking dogs, and find somewhere that’s all-but silent except for the chirping birds (tame goldcrests!) and lapping waves.

Construction work, of course, is sometimes necessary. And as annoying as a neighbour’s incessantly barking dog can be, most of us don’t want Kristi Noem for a neighbour either. As evidence that Silba lacks reasonably strict noise ordinances, though, I submit one piece of evidence: gas-powered leaf blowers exist there On the same note, I might add that if islanders’ gardens are haunts for peaceful passerines, this too may be de facto rather than de jure. I cannot comment on the practices of all islanders, of course, but wildlife-friendly gardening did not seem to be trending on my block. The following is another anecdote I posted on my personal Facebook account:

This afternoon, I was sitting on my terrace [...] when I was pleasantly distracted by a very sweet Fuglekonge [goldcrest] (Regulus regulus) in the garden, one of the tamest Fuglekonger I’ve ever met. The tiny bird was hopping and fluttering about from dandelion stem to dandelion stem, foraging in the seed heads, sometimes succeeding, sometimes losing his balance, sometimes finding the prize out of reach. It was one of multiple moments of great regret for not bringing my Nikon, but I thoroughly relished his company nonetheless. [...] Then, without warning, a man from the neighbour’s property tramped across the Fuglekonge’s foraging grounds, and he reached down and uprooted a handful of dandelions as he passed. The man soon reappeared on the neighbour’s lot with his loud-ass appliance of vegetational destruction, utterly drowning out the chirping of the Fuglekonger, Robins, and Black Redstarts. In fact, the noise was completely insufferable [...] so I left. When I returned to my apartment, I was immensely saddened but not at all surprised by what I found: every last dandelion on ‘my’ property had also been destroyed, including those that the beautiful Fuglekonge had been so intently browsing just a couple of hours prior.

This anecdote shall also serve to bring us back to the beginning: out of all the places I’ve been without my “real camera,” Silba is where I missed it the most…

5. Those Goldcrests, though…

When I arrived for my sojourn in Silba, I was greeted by a delightful lifer: an abundance of friendly Black Redstarts (Croatian: mrka crvenrepka). The Goldcrests (Croatian: zlatoglavi kraljić) came a few weeks later, and they came in droves. Just as I was beginning to feel a bit lonesome in my linguistic isolation, these cheery little birds boosted my mood. Goldcrests were no lifers to me, and as Europe’s smallest birds they are inevitably cute, but I have never seen the species nearly as abundant, nor its individuals nearly as tame and cheerful — almost personable — as on Silba.

Spend enough time on remote islands, and idyllic beaches and views of the Milky Way start to feel like a dime a dozen (a biased perception, to be sure, and not necessarily a good one for a conservationist); go to Northern Europe to enjoy them with better coffee and less cigarette smoke. But those Black Redstarts! And those Goldcrests! And that damn camera I’d left all the way across an ocean and large chunks of two continents… Those were the things that lingered on my mind after leaving Silba.

And so it was that many months after I’d told people that I’d left Croatia for good, I found myself divulging little hints like, “Weirdly, I recently had a vague and fleeting thought ‘I should return to Silba to photograph tame goldcrests,’” and “The vast majority of the time, I did not regret travelling without my camera. But, of course, what I remember are those small minority of times when I wish I’d had it – such as the black redstarts and unusually tame goldcrests on Silba.”

Would I go back to Silba for goldcrests (and black redstarts)? Would I attempt to track down the flock elsewhere? If I did either, did I succeed? And why did I used to refer to goldcrests as ‘Fulgekonger’ anyhow? Stay tuned to Nonmotorized Trails to find out the answers to these questions, amid other anecdotes of car-free exploration.